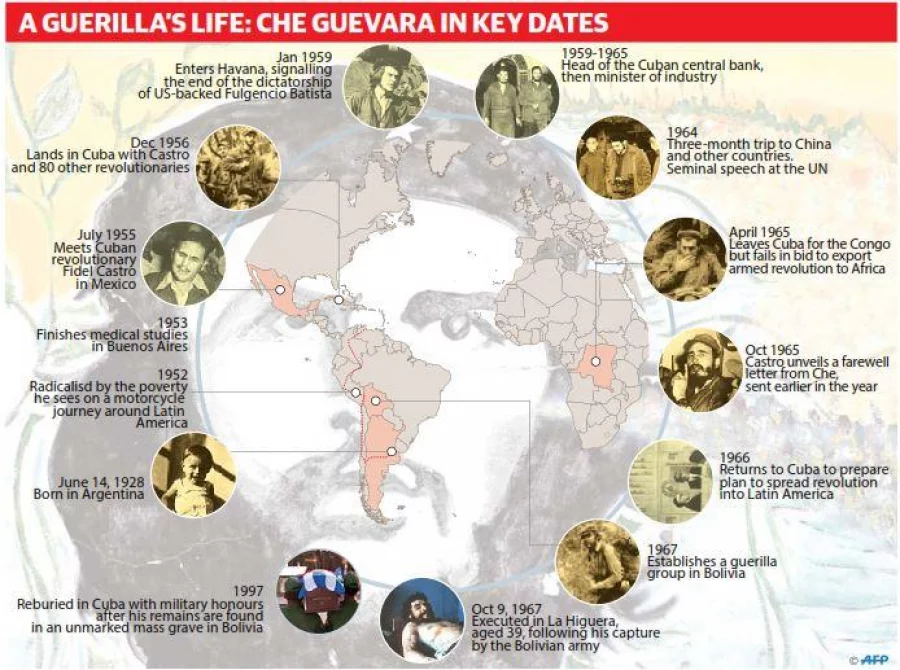

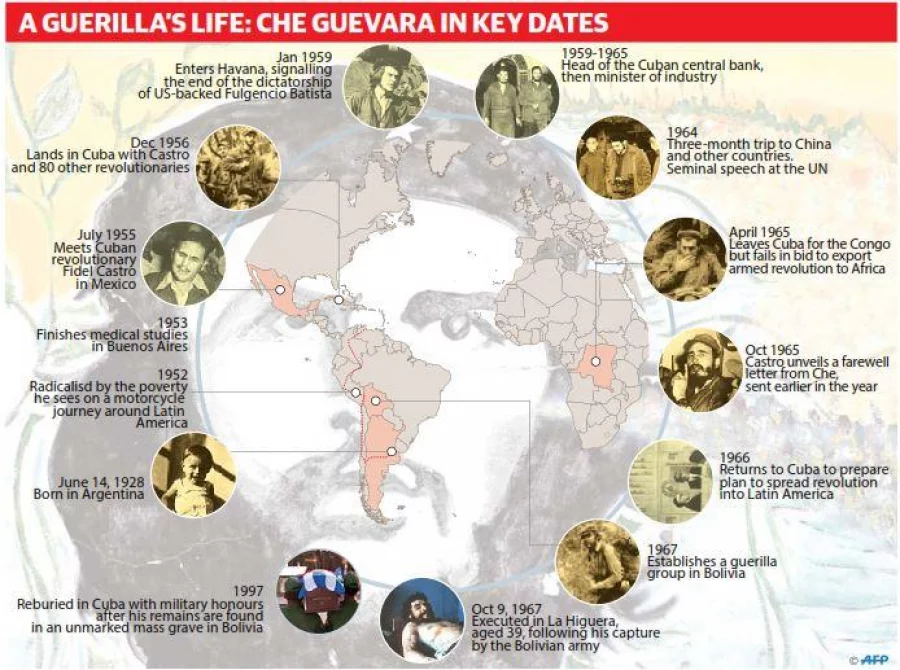

On November 3, 1966, a middle-aged Uruguayan businessman named Adolfo Mena Gonzalez touched down in La Paz, Bolivia. He took a hotel suite overlooking the snowbound heights of Mount Illimani, and photographed himself - overweight, balding, lit cigar in his mouth - in the mirror.

In reality, however, he was none other than Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentina-born revolutionary who helped topple Cuba’s US-backed dictator, lectured the United States from a UN lectern, penned treatises on Marxism and guerilla warfare, and sought to export socialism worldwide.

Eleven months later, another image of Guevara would spread around the world, showing his scrawny, lifeless body on a stretcher, his full head of hair and beard unkempt, and his eyes wide open.

The Christ

“They said he looked like Christ,” said Susana Osinaga, 87, a retired nurse who helped wash the dirt and blood off Guevara’s body. “People today still pray to Saint Ernesto. They say he grants miracles.”

Monday marks the 50th anniversary of Guevara’s death on October 9 1967, an event which Bolivia’s current left wing president, Evo Morales, will commemorate with a host of events including a “Relaunching of the Anti-Imperialist Struggle”.

But the date is also prompting less triumphant reflections on Guevara’s legacy at a time when the Latin American left, guerrillas and democrats alike, is in full retreat.

After a failed expedition to the Congo in 1965, Guevara alighted on Bolivia as the launchpad for regional, then global, revolution. “In retrospect you can perceive a certain naivety; an almost crass idealism,” Jon Lee Anderson, author of the definitive 1997 biography Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, told the Guardian.

But in the febrile atmosphere of the 1960s, anything seemed possible. “If there was ever a time in the modern era to pull something like that off, it was then,” Anderson added.

Yet things went wrong soon after Che and his column of 47 men arrived in the arid, thorny Nancahuazu region. They lost radio contact with Cuba, supplies ran low. They were plagued by illness and vicious insects.

The Bolivian recruits resented taking orders from the battle-hardened Cubans, and government propaganda sowed fear of the foreign interlopers among the campesinos. The US soon got wind of Guevara’s presence and sent CIA agents and military advisers to assist the regime of Rene Barrientos.

'I am Che'

On August 31 an army ambush wiped out half of Che’s forces. The remainder trudged towards the mountains in a desperate attempt to break out of the trap.

Che, prostrated by asthma, rode on a mule towards the remote village of La Higuera. A local farmer informed on them – and amid a frantic gunfight, a bullet destroyed the barrel of Guevara’s carbine. Wounded, he surrendered to a battalion of rangers, trained by US Green Berets, under the command of a 28-year-old captain, Gary Prado.

“Don’t shoot - I’m Che. I’m worth more to you alive,” Guevara reportedly said.

'Get rid of him'

Guevara and his captured comrade, Simeon “Willy” Cuba Sarabia, were escorted to La Higuera and held in separate rooms of the schoolhouse. Prado had several conversations with Guevara, and says he brought him food, coffee and cigarettes. “We always treated him with respect. We had nothing against him even though we had [had] soldiers killed,” he claimed.

When Guevara asked what would happen to him, Prado said he told the guerilla that he would be court-martialled in the city of Santa Cruz.

“He found it interesting, the idea that he might have a chance in court,” Prado said.

The trial never happened. According to Prado, orders came the next day to “get rid of him”.

A 27-year-old army sergeant, Mario Teran, volunteered for the job, and ended Guevara’s life with two bursts of machine-gun fire. After being flown by helicopter to nearby Vallegrande and displayed for the world’s press, Che’s body – minus his hands – and his companions were buried in unmarked graves. They wouldn’t be found for 30 years.

Although Prado insisted he had no role in Guevara’s killing, he maintained that such conduct was common at the time, citing the judicial executions overseen by Guevara after the Cuban revolution.

“He was executed, that was reprehensible. But you have to think about things at the moment that they happened … in that moment, it was justified,” he argued.

Today, bullet marks score the rocks where most of Guevara’s Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN) comrades were gunned down. The boulder behind which Che sheltered is daubed with graffiti.

The myth of 'Che'

With his death, at the age of 39, the myth of "Che", the personification of rebellion, was born.

Fidel Castro called him an "artist of revolutionary warfare" in a speech to an estimated one million people during a three-day period of national mourning.

In time, through T-shirts, posters and berets bearing his iconic image, he became a symbol of the capitalist consumer society he sought to destroy.

"Myths exist because societies create them," said his 74-year-old brother. "What other mythical character is there? I would say that the two most famous images in the world are those of Christ and Che.

"A friend told me: 'you're exaggerating, Christ is much better known.' Of course. He died 2,000 years ago, and Che 50 years ago. We will not be there to see it, but Che in 300 years, will always be Che. And I hope there will be other Che's."

Born in the Argentine city of Rosario, Guevara traveled across Latin America in 1952 and 1953 and was shocked to see the economic disparity in the region, a road trip that was immortalized in the 2004 film "The Motorcycle Diaries."

It convinced him violence was necessary to overturn Latin America's unjust social order.

His life changed dramatically when he met Castro in Mexico in 1955 and joined his guerrilla expedition to Cuba.

In the early 1960s, he worked with Castro to consolidate the revolution, supervising the repression of counter-revolutionaries, and even for a time heading the Central Bank and industry ministry.

But his key motivation was to spead revolution elsewhere.

Exporting revolution

In 1965, he bid farewell to Cuba in a letter to Castro in which he resigned his posts and wrote: "other nations of the world summon my modest efforts of assistance."

After leading a group of Cuban revolutionaries fighting with Marxist guerrillas in the Congo, Guevara traveled to Bolivia in late 1966.

Struggling with asthma, he led a small clutch of rebels in Bolivia for 11 months trying to spread revolution but was tracked, cornered and wounded in the mountains in a gunbattle that wiped out most of his remaining rebels.

The Bolivian army and two Cuban-American Central Intelligence Agency agents captured him. He was executed in a schoolhouse in La Higuera the following day, October 9, 1967. The small revolution he started in Bolivia died with him.

The army exhibited his body as a trophy in the nearby town of Vallegrande, and press pictures went around the world, the myth-makers making reference to his Christ-like features.

Three decades later Cuba came to a standstill when Fidel Castro had the remains of his old comrade dug up from his mountain grave and brought back to Santa Clara to lay to rest in the mausoleum. Across the world, the images revived the myth for a new generation.

"Why did he not remain a minister in Cuba? Is was not his objective in life, he was not the kind to sit in an office," said Juan Martin Guevara.

"What he would have become, it's impossible to know. He would always have been on the side of struggling peoples."

Sources: Guerrillero, Havana Times, Guardian, AFP